A mother stands in her living room, surveying the damage. Her eighteen-year-old son has just been arrested. To justify the arrest, the soldiers overturned the house, searching for anything that could be used as evidence. In the youth’s bedroom they found a pocket knife. There was no warrant. No warning.

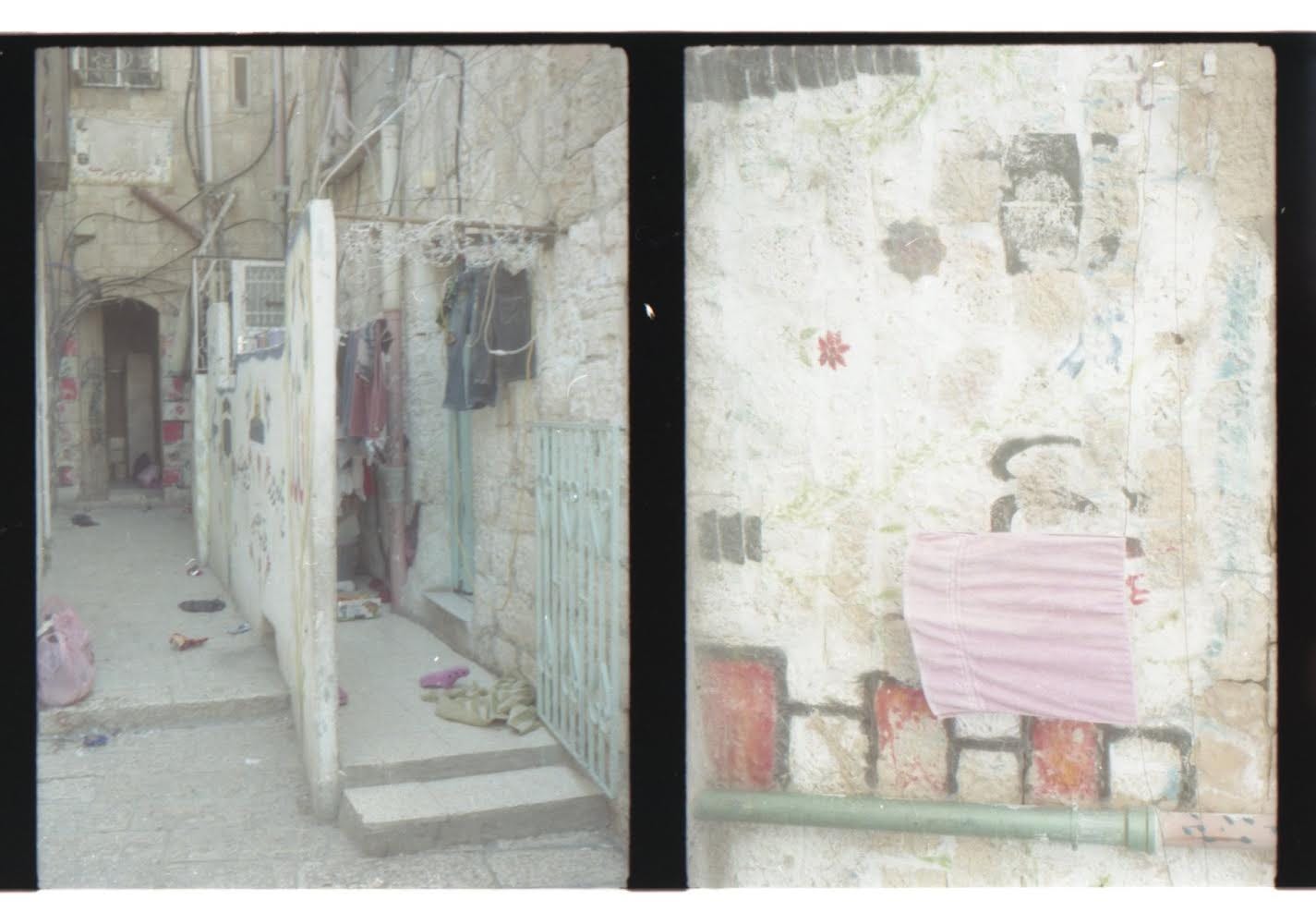

Anemone Delvoie is a mother and ceramicist based in Big Sur, California. She took this photo in Palestine’s West Bank in 2010 while participating in an artist-led summer camp for local children and young people.

“I went with a Belgian organization, during the summer. We set up an art summer camp in a school in the West Bank. It was so moving and shocking and educating for all of us.

We were a group of about 10 young artists teaching the camp and for most of us it was the first time in Palestine.

The kids, the families and Palestinian teachers were amazing, so joyful and welcoming…they are a really warm and hopeful people.”

Anemone’s photos, shot both digitally and on film, are more than snapshots. They form a collection of delicate impressions, granting softness to a subject rarely afforded such grace from an outside perspective. The pictures document a personal encounter with a steadfast place and people that have been continually misunderstood, misrepresented, and marginalised for decades in Western media and politics.

The photo of a mother standing in the wreckage of her home following the arrest of her son feels different. A kind of access has been granted. It’s a different kind of wreckage to the kind we’re now seeing out of Gaza, but one that speaks equally to displacement and oppression.

Violence in the West Bank had escalated since the October 7 attacks.1 2023 has been the ‘deadliest’ year for Palestinians in the West Bank since 2006, according to the United Nations.2 Armed Israeli settlers, emboldened, have been attacking Palestinian villages at night, breaking into homes, destroying belongings, and terrorizing families.3 In recent weeks, the village of Zanuta was finally abandoned by its 150 residents, who made the collective decision to leave after decades of unrelenting harassment and violence.4 In areas of the West Bank as in Gaza, people say this is ‘the new Nakba’.5

Since the Israel-Hamas prisoner exchange began a few days ago, Israel has arrested almost as many Palestinians as it has released.6 The majority of those released can be expected to be rearrested, be it within days, weeks, months, or years.7 Many of them are children.8

Reading about Israel’s arrests of children, often on the flimsy, sometimes fabricated charge of stone-throwing, I am reminded of the detainment of Aboriginal children in Australia. I am also reminded of the abuses these children face at the hands of police and prison guards. The excessive, often lethal force. A quick Google search for ‘Aboriginal child arrest’ yields these results — all discrete cases, all reported within the last 18 months:

Aboriginal 18-year-old with disability thrown to ground during NSW police arrest while having seizure (17th August, 2023), NSW cop found guilty of assaulting Aboriginal boy (28th November, 2023), NSW police to review arrest that left 14-year-old boy’s face covered in blood (16th September, 2022), Man charged with assault of Indigenous child who had been restrained by Barkly Regional Council mayor (9th November, 2023).

Those are just the first four results.

In the occupied West Bank, Palestinians — including children — face a military judicial system, while Israeli settlers are tried in civilian courts inside Israel.9 This judicial disparity is a form of apartheid10, and has been condemned by Israel’s largest human rights group.11

Fadi Quran, Campaign Director of online activist network Avaaz, recently shared his own illustrative account on X; I urge you to read it.

I want to return to the mother in the photo. I want to tell you what happened to her son. I can’t.

I’m thinking often of this poem by Mosab Abu Toha, who was recently abducted by Israeli forces in Gaza.12 At the time of his arrest he was holding his three-year-old son, Mostafa, as he and his family attempted to enter Egypt at the Rafah checkpoint. He has since been released, after being forced to hand over his and his family’s passports, including his son’s US passport. The IDF also confiscated his clothes, his children’s clothes, his wallet, his credit cards, and all the money he had on him. Nothing was returned.13

His poem is called Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear, and is dedicated to Alicia M. Quesnel, MD.

While eyes are on Gaza, it’s important to also keep our eyes open to the West Bank. Anemone Delvoie’s images are a beautiful glimpse.

You can support Anemone’s work directly by purchasing a print. All proceeds go to Medical Aid for Palestinians (MAP).

You can download Mosab Abu Toha’s book, Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear, for FREE here, until December 5. That link also gives you access to a lot of other useful publications during Read Palestine Week.

Beautifully written, Hannah. 🩷